Problem-Solving Model Using Personality Type (Part 2: The Z-Model Ideal vs Actual)

When people have been presented with the same information, have you ever wondered how they can come to such different conclusions? Have you noticed that some people are quick to decide, whereas others take much longer? Personality type may play some part in these problem-solving differences. In this two-part series, Dr. Yvonne Nelson-Reid explains Gordon Lawrence’s Z-Model for problem-solving using personality type.

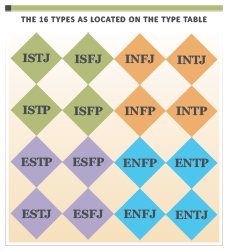

In the first article, Problem-Solving Model Using Personality Type (Part 1: The Z-Model), Gordon Lawrence’s (1979/2009) Z-Model was introduced. An overview of how to use the model for effective problem-solving was provided, along with questions relevant to each of the mental processes (Sensing, Intuition, Thinking, Feeling) to help guide you on how to access your stretches (those mental processes not included in your four-letter MBTI® type code) alongside your strengths (the two middle letters found in your type code).

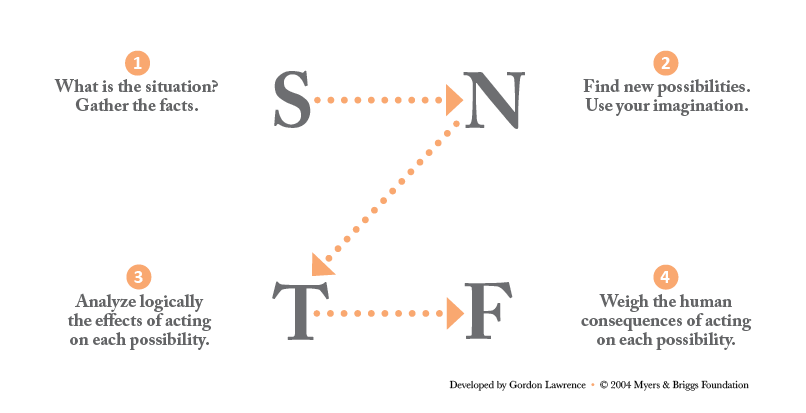

The suggested problem-solving model follows a Z pattern, working through the preferences in the sequential order of S, then N, then T, then F: Sensing and Intuition for taking in information, followed by Thinking and Feeling for deciding, with each type typically leaning into those preferences they are most comfortable with while likely neglecting those they are not. The Z-Model, as figure 1 shows, was created as an aid to promote balanced problem-solving. But is this really how our natural problem-solving styles work?

FIGURE 1. The Z-model.

In this second article, Part 2, personality type bias is considered. Yes, we all have bias when it comes to our personality type preferences, often unconsciously. We tend to trust our own preferences and doubt others. Because type is developmental, this is most obvious with younger people or adults whose type preferences are less developed or where there is a lack of self-awareness.

Type Dynamics and Development

Type dynamics and development help explain our natural personality type biases. Young people naturally tend to lean on their dominant mental process the most, using it in the world they feel most comfortable in—Extraversion or Introversion (e.g., introverted Thinking for INTP preferences). As they mature, they begin to build comfort in using their auxiliary mental process (e.g., extraverted Intuition for INTP preferences). However, it often isn’t until adulthood and, in many cases, midlife that people gain the ability to use their non-preferred processes, the tertiary (e.g., introverted Sensing for INTP preferences) and inferior (e.g., extraverted Feeling for INTP preferences) mental processes, and some never do. Going into depth on type dynamics is beyond the scope of this article. If interested, you can read more about type dynamics and development at myersbriggs.org.

What is important in this article is to understand that for each type, there is a natural order of development and ease of access in using the perceiving (Sensing or Intuition) and judging (Thinking or Feeling) mental processes—the natural order being from the dominant to auxiliary to tertiary to inferior mental processes. It is through this understanding of type dynamics, as Lawrence suggested, that most types naturally approach problem-solving. Simply stated, type dynamics demonstrates the way each of our preferences interacts, the probable path for development, and the order in which they are accessed. For instance, someone with a preference for ESFJ (Extraversion, Sensing, Feeling, Judging) tends to trust their Feeling (dominant) preference the most, followed by Sensing (auxiliary), then Intuition (tertiary), and lastly, the Thinking (inferior) preference. Each of these processes is either introverted or extraverted, adding another layer of complexity—a nuanced problem-solving approach that will not be addressed in this article.

Lawrence touched on the role of the Extraversion–Introversion and the Judging–Perceiving preferences in problem-solving. Extraversion considers environmental influences on the problem, making sure there are action plans after the decision is made, and Introversion wants clearly understood ideas and concepts. He also described how the Judging preference wants to get closure on the options and make the decisions, whereas the Perceiving preference wants to keep the options open to find new possibilities. Katherine Hirsh and Elizabeth Hirsh (2007) provide clear guidance on this complex topic in their book, Introduction to Type and Decision Making, for those of you wishing to learn more.

Ideal vs Actual Problem-Solving

Type dynamics can affect how one naturally approaches the Z-Model and how much energy and focus goes into each of the mental processes. Ideally, each process would be accessed sequentially in a balanced way, following the Z pathway (S–N–T–F). However, since each type favors some processes more than others, Lawrence acknowledged that balance is rarely achieved. Rather, this ideal sequence may look quite different when taking the uniqueness and bias of the mental processes for each of the 16 MBTI types into consideration, which alters how much energy goes into each mental process and the order in which they are actually accessed.

Lawrence saw that people are more likely to lead with their natural styles and may get stuck in one area while avoiding others. For example, someone with an ENFP preference may only use the Intuition and Feeling processes (NF strengths) when problem-solving and miss out on important facts and an objective view (ST stretches). On the other hand, people who prefer ISTJ may rely on the Sensing and Thinking processes (ST strengths) without considering other possibilities and the impact the decision might have on other people (NF stretches).

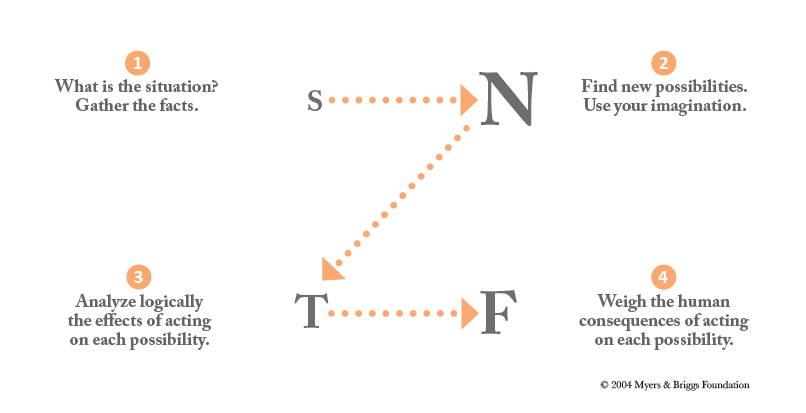

Example: The Z-Model for ENFP Preferences

To extend the example, those who prefer ENFP may skip Sensing, begin with Intuition, not consider Thinking, and jump directly to the Feeling preference, which doesn’t follow the Z pathway of S–N–T–F. People tend to rely on their strengths while neglecting their stretches; they naturally rely on their dominant process, which leads to poor decisions.

In the diagram (fig. 2), the letter size from large to small represents the order of the mental processes—what gets the most attention to the least (dominant to auxiliary to tertiary to inferior process); the bolded preferences highlight where each type may naturally spend most of their time. The diagram (fig. 2) represents how someone with ENFP preferences might naturally approach decision-making. They tend to trust their NF preferences and may neglect the ST preferences.

FIGURE 2. The Z-model showing the natural order one with ENFP preferences might approach when using their mental processes.

What is your type’s bias in problem-solving?

Each of the 16 MBTI types uses the same four steps to solve a problem; however, each type typically has a pattern for using these four steps. Some steps come naturally. Other steps may seem more difficult and may even be overlooked entirely.

According to Lawrence, without type awareness, each personality type will likely follow its own biased path to problem-solving. Although S, N, T, and F create the Z in the Z-Model, not everyone follows these steps in that order. We tend to lean on our natural type preferences while neglecting the others.

How do I use the Z-Model?

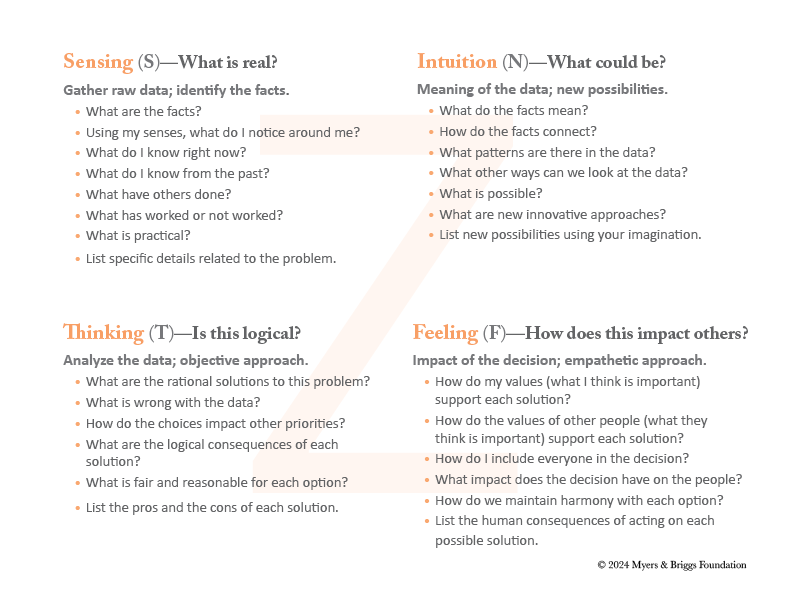

First, know your own problem-solving bias. Trust your strengths, the middle letters of your MBTI personality type code, and use the list of questions (fig. 3) to help you with your stretches, the opposite preferences, for a more balanced approach to decision-making.

FIGURE 3. Type related questions to support balanced problem-solving.

Find your problem-solving bias based on your MBTI personality type in the supplemental PDF—Z-Models for the 16 MBTI Personality Types—and practice using the Z-Model as a tool to support effective and responsible decision-making! Let us know how it works for you!

Hirsh, Katharine W., and Elizabeth Hirsh. 2007. Introduction to Type and Decision Making. Mountain View: CPP, Inc.

Lawrence, Gordon. 2009. People Type & Tiger Stripes: Using Psychological Type to Help Students Discover Their Unique Potential. Gainesville: Myers & Briggs Foundation, Inc.

_thumb.png)